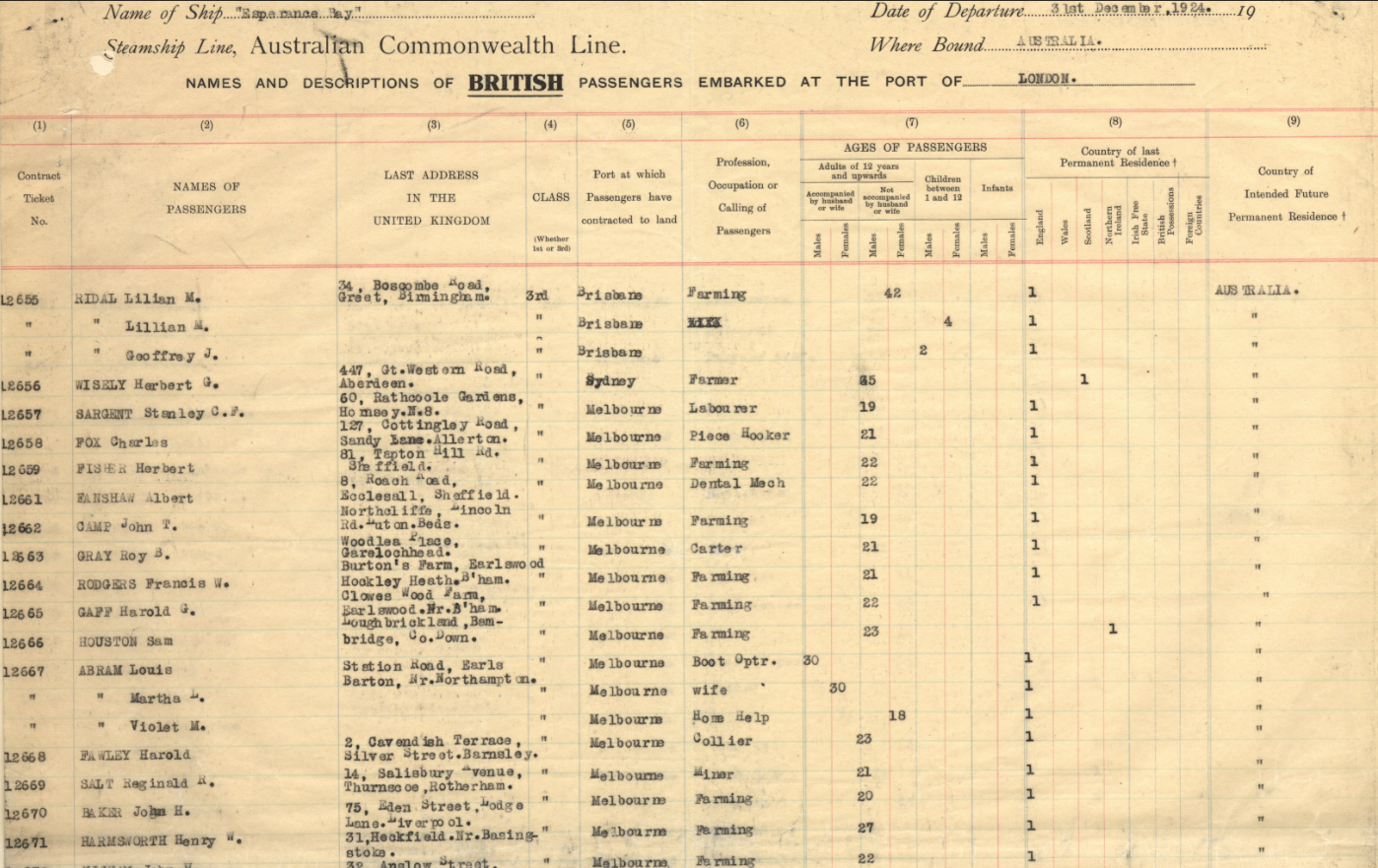

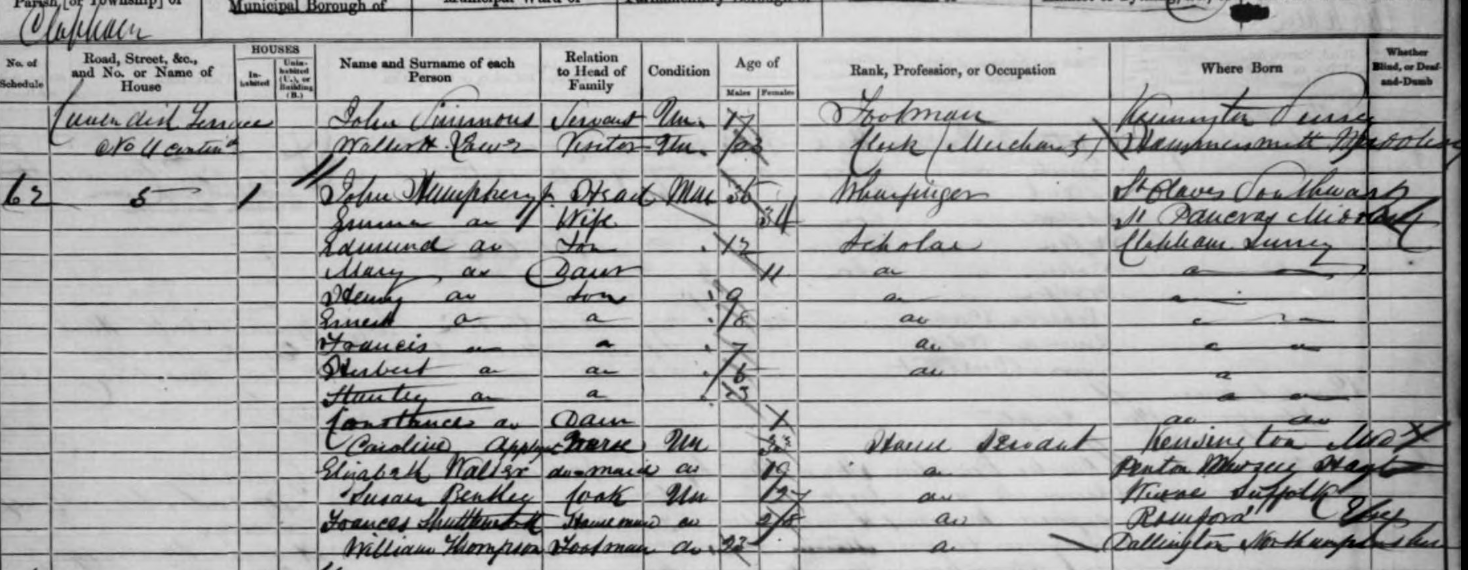

John was born in St Olave’s Southwark in 1825. On the 1851 census, aged 24, he is living at 5, Cavendish Terrace, Clapham, Wandsworth, London and Surrey, England with his wife Emma. His occupation is given as Wharfinger (the term means keeper or owner of a wharf and is pronounced wor-fin-jer). Ten years later on the 1861, John and Emma can be found at the same address, now with eight children (Edmund, Mary, Henry, Ernest, Francis, Herbert, Stanley and Constance) and five servants, including a William Thompson, born in Dallington, Northamptonshire, (who I believe is possibly the father of my great grandfathers first wife), employed as a footman.

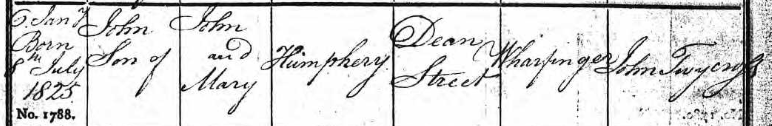

Baptised on 6 January 1826, in Bermondsey, St Olave, Southwark, John was the son of John and Mary Humphery who were living at Dean Street. On the baptism certificate the occupation of John’s father is given as Wharfinger too.

On 5 October 1847 John married Emma Cubitt at St Leonard, Streatham, Lambeth, England. John’s profession is given as Squire, John’s father is named as John Humphrey, Alderman of London and Emma’s father is named as William Cubitt, Sheriff of London.

The Tallow Chandlers Association

On learning about John Humphery I contacted the Tallow Chandlers Association to see what more I could learn and they advised me as follows.

Between around 1760 and 1938 there were at least four John Humphery’s two of whom were Alderman. The first was John Humphery, a soap boiler from Shadwell and the first of the Humphery’s to become a member of the Tallow Chandlers’ Company – his father, William Humphery, was also in the tallow trade importing oil and fats to Hay’s Wharf in the 1960s.

The second John Humphery was the famous Alderman Sir John Humphery (1794 – 1863) who was MP for Southwark from 1832 to 1852, Sheriff of London and Middlesex in 1832, and Alderman for Aldgate in 1836. He was also Master of the Tallow Chandlers’ Company in 1838 and 1858. This John was in control of Hay’s Wharf from 1840 and commissioned William Cubitt (the father-in-law of two of his sons – John Humphery and Sir William Henry Humphery), to design and build new warehouses in 1856.

The third John Humphery (1825 – 1868) was one of six sons (that are have listed on the database) of Alderman Sir John Humphery and was known as John Humphery the younger on our records.

The fourth John was Lt. Col. Alderman Sir John Humphery (1872 – 1938). He was born to James Arthur Humphery (son of Alderman Sir John Humphery (1794 -1863) and brother of John Humphery the younger (1825 – 1868). Among his many accomplishments, this John was Sheriff of London in 1913, Alderman for Tower Ward and Master of the Tallow Chandlers’ Company in 1919 and 1926. He fought in the First World War and according to a comment on his record – was temporarily appointed Town-Mayor of Ypres when his regiment was divided into several independent squadrons and had no one left to command. He was also awarded various medals as a result of his service

British History Online

Port of London Study Group

An article about Hay’s Wharf by Gillian Barton on the Port of London Study Group website writes about the the Humphery and Cubitt families too, stating:

‘In 1840 the wharf came under the control of John Humphrey Junior, an Alderman for the City of London, Master of the Tallow Chandler’s Company, Lord Mayor of London in 1842, MP for Southwark 1832-52 and proprietor of Hay’s wharf from 1838 – 1862. In 1856 he commissioned William Cubitt to design and build new warehouse accommodation. He created a small inland dock so barges could gain access from the river, with a five storey warehouse on each side of the new dock. Business was good, until the Great Fire of Tooley Street in 1861. Described as ‘the greatest spectacle since the Great Fire of 1666’, it destroyed the “best warehouses in the kingdom”. The fire started at Cotton’s Wharf, destroying 11 acres of land. London Bridge railway station also caught fire in the blaze. Most of the wharves were rebuilt in the late 1800s as a result of Humphrey’s partnership with Smith and Magniac (whose company later became Jardine Matheson).’

Other information

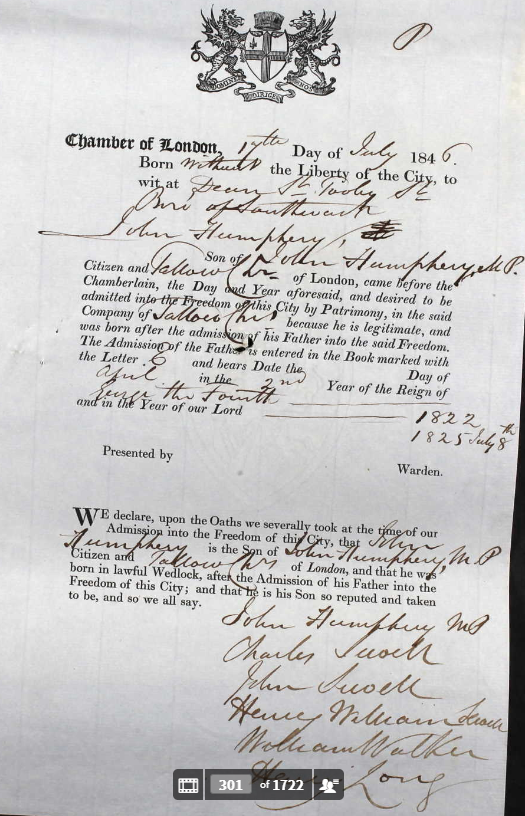

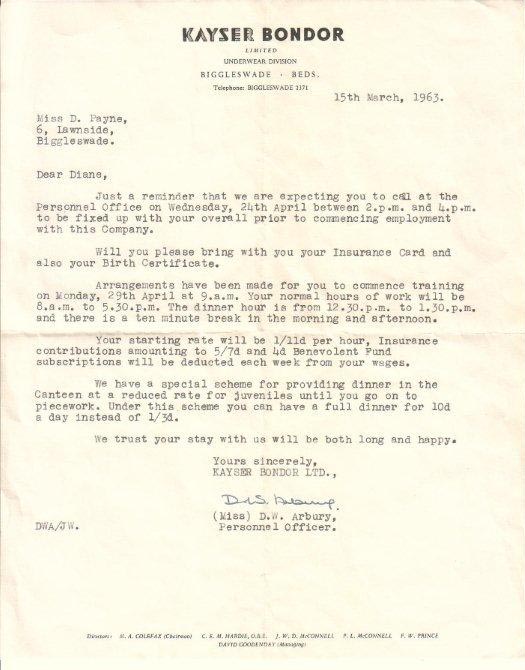

Freedom of the City Admission document for John Humphery.

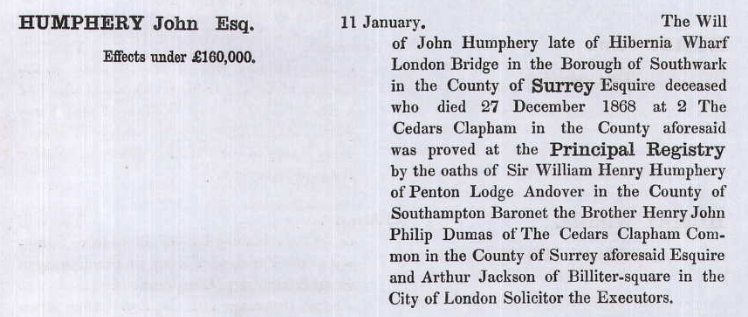

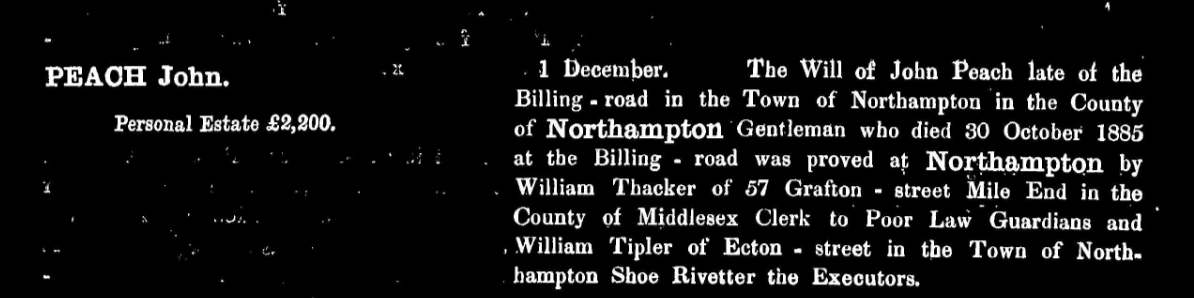

The will of the second John Humphery recorded by the Tallow Chandlers Association was proved on 11 December 1868.

Sources

Further information

Street directories

- London Robsons Street Directory for Tooley Street, Southwark: 1832 (see entry for Hays Wharf)

- Tooley Street, Southwark: 1842 street directory (see listing for Hays Wharf)

- London Street Directory, 1843 (see entry for Humphrey, John)

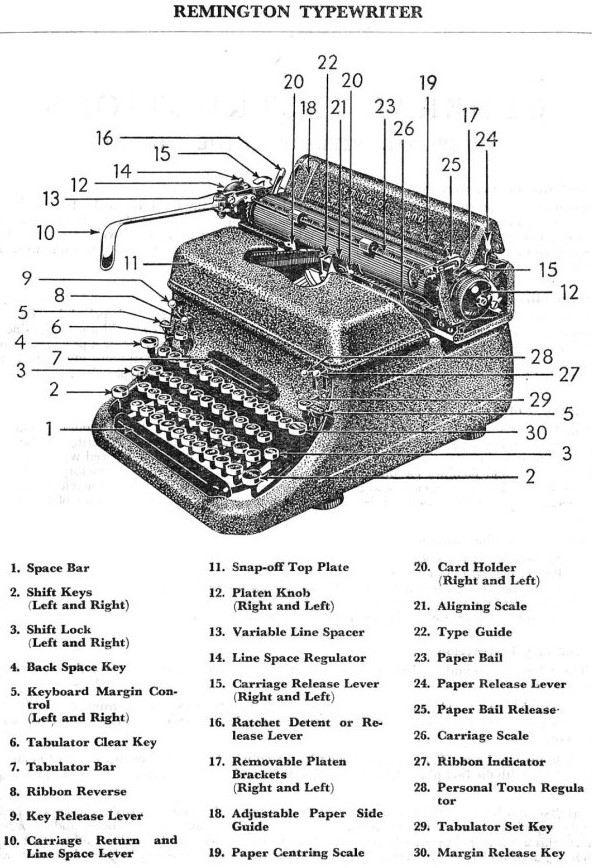

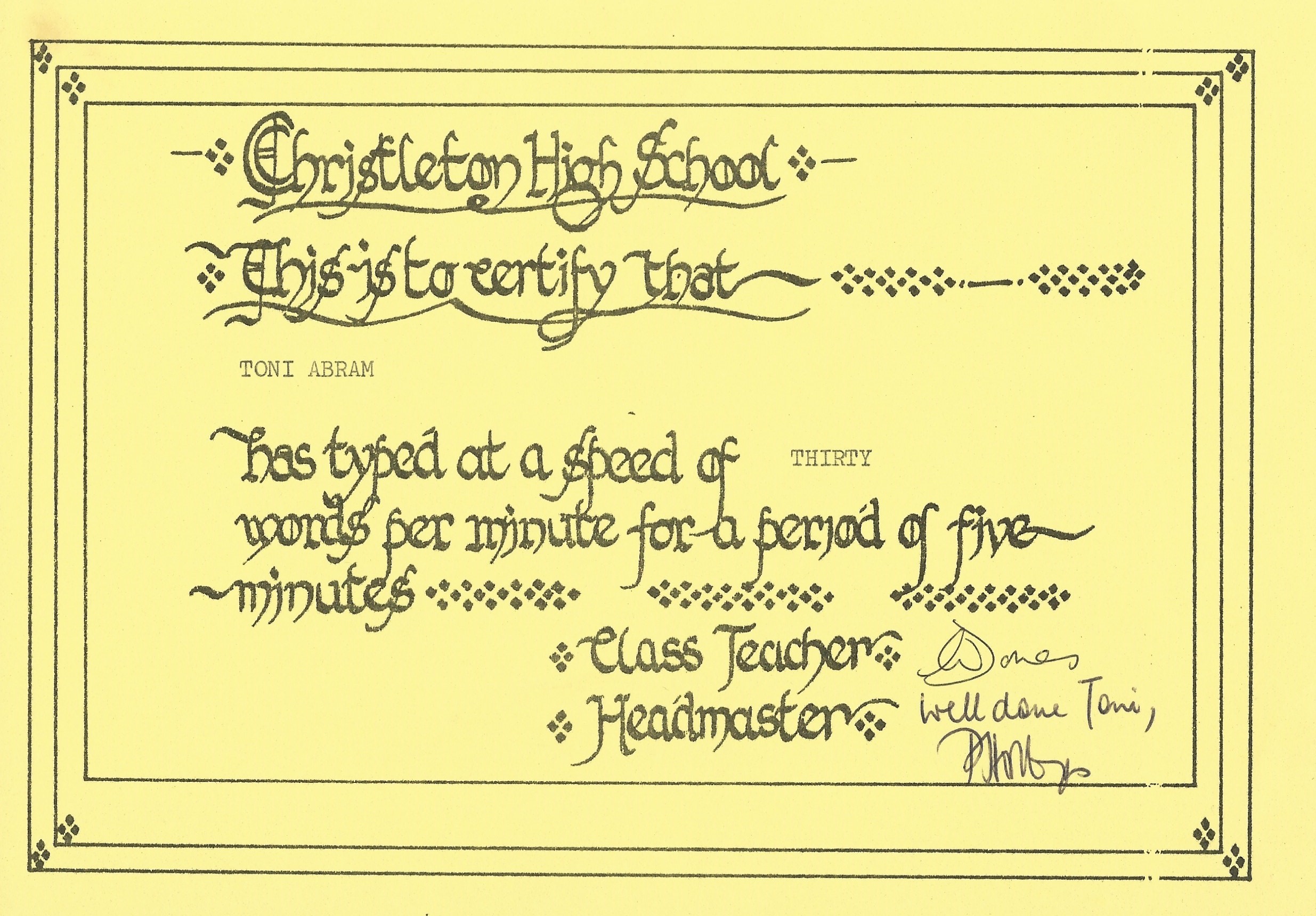

Speed test certificate.

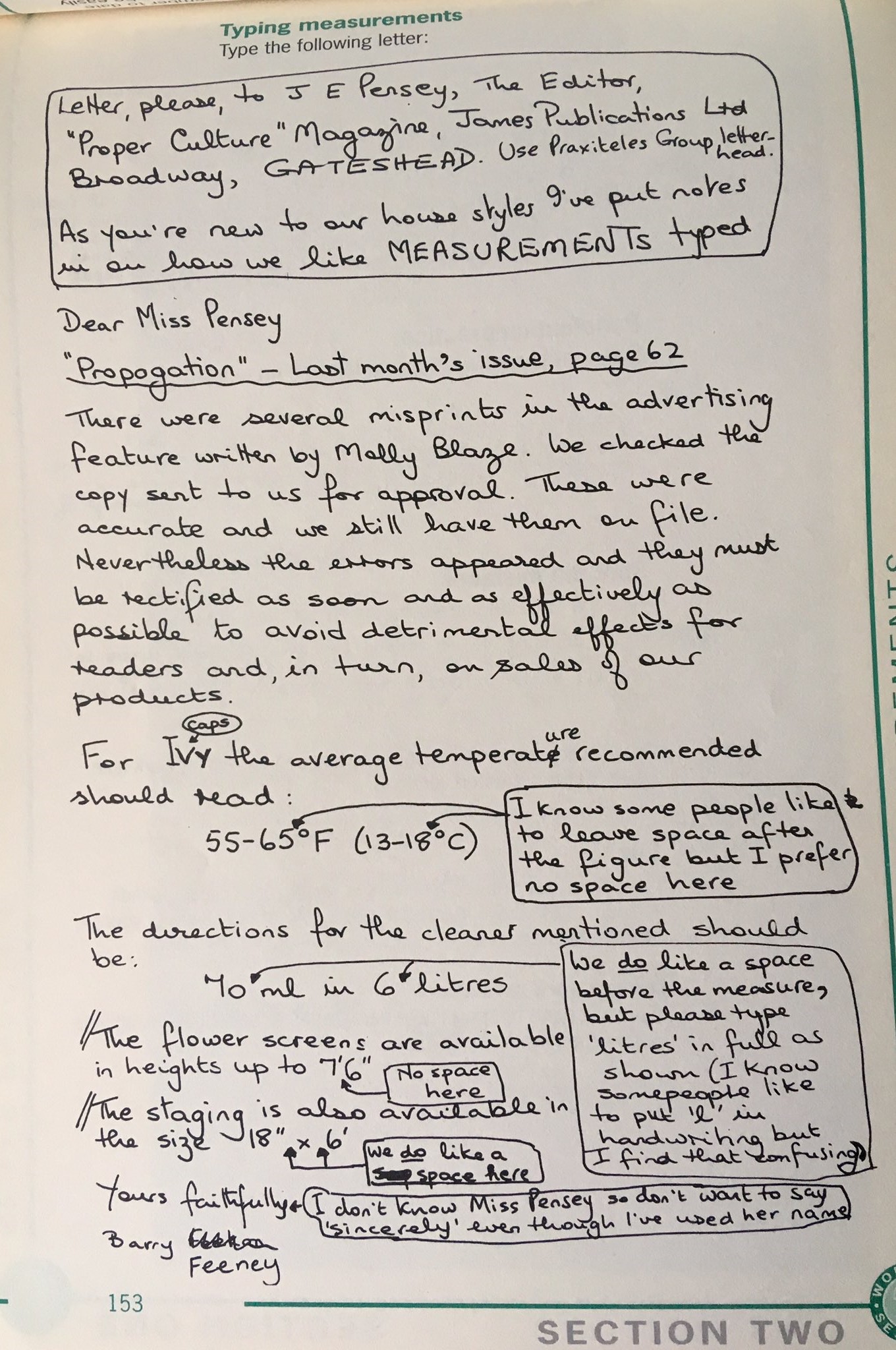

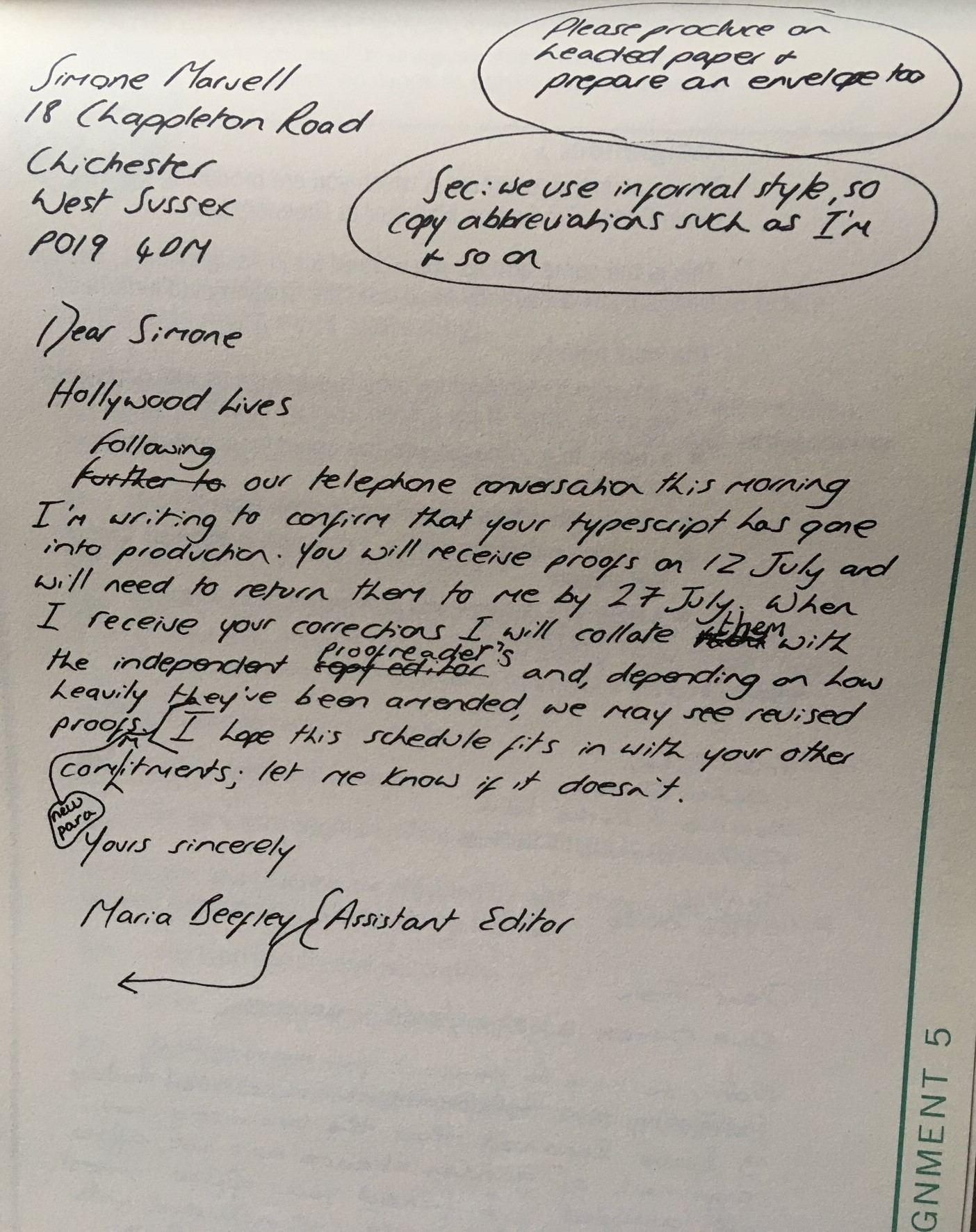

Speed test certificate. Example of an instruction to type a letter.

Example of an instruction to type a letter.